communicator a deaf/blind person?

Because Helen Keller was a master of perseverance, willing to take risks, widely admired, smart, accomplished, a pioneer. In The Story of My Life, we learn that accommodation doesn't mean charity

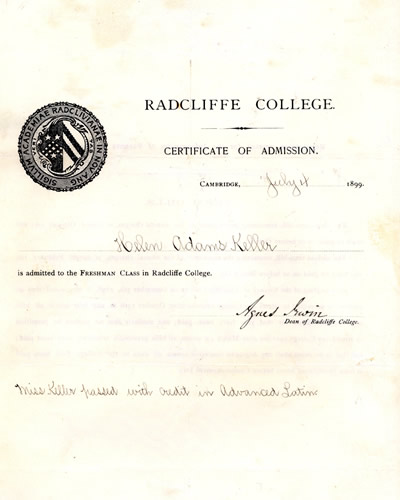

Perhaps an explanation of the method that was in use when I took my examinations will not be amiss here. The student was required to pass in sixteen hours--twelve hours being called elementary and four advanced. He had to pass five hours at a time to have them counted. The examination papers were given out at nine o'clock at Harvard and brought to Radcliffe by a special messenger. Each candidate was known, not by his name, but by a number. I was No. 233, but, as I had to use a typewriter, my identity could not be concealed.

It was thought advisable for me to have my examinations in a room by myself, because the noise of the typewriter might disturb the other girls. Mr. Gilman read all the papers to me by means of the manual alphabet. A man was placed on guard at the door to prevent interruption......athlete a wheelchair user?

Because Bob Hall, who was the first wheelchair entrant in the Boston Marathon in 1975 (2 hours 58 minutes) stood up for himself and won. And nowadays most wheelchair marathoners wait an hour at the finish line for the first sneakered finishers.

The rejection of entrants in wheelchairs for the New York City Marathon has stirred a controversy among officials and competitors affiliated with the Oct. 23 race.

A record 5,000 runners have been approved for the five‐borough marathon, including applications from competitors who are blind and wear artificial limbs. But the New York Road Runners Club rejected the entry of Bob Hall of Belmont, Mass., and others in Wheelchairs on the ground that their participation constituted a safety hazard during the race.

“We do not want to jeopardize your safety and that of other participants,” Fred Lebow, the president of the ,New York Road Runners Club, wrote in a Sept. 12 letter to Mr. Hall. In the letter he cited a hazardous route—“five bridges with very narrow ramps”—as the main reason for the rejection.

Mr. Hall, who competed in the Boston Marathon last spring, has refused to accept the rejection and has called on the New York Civil Liberties Union to assist his case.

“The safety question is really very frivolous,” the 25‐year‐old Mr. Hall said when reached at his home, where he was preparing to leave for another marathon race last weekend in Virginia. “I've been competing with runners for years and demonstrated my ability.”

Chris Hansen, a lawyer for the New York Civil Liberties Union, said he viewed the dispute “the same way as I view race and sex discrimination.”

“Think how you would feel about running 26 miles or wheeling 26 miles,” Mr. Hansen said. “This is not an electric wheelchair. You have to push yourself every inch. It's an incredible tribute to Bob Hall that he can achieve what he has as a competitor.....composer deaf?

“We are actively trying to resolve it out of court. When those avenues are exhausted, then we may have to go to court.”

Federal regulations were approved earlier this year prohibiting any discrimination against the handicapped. Efforts to upgrade programs for handicapped athletes were included in the recommendations of the President's Commission on Olympic Sports.

“The differences in the problems of the handicapped versus those of the able‐bodied,” the commission noted in its recommendations, “are differences only in degree and dissimilar only in the particulars of the individual situation. Essentially all are alike. Only the perceptions provide a contrast.”

Because the Pastoral Symphony never disappoints.

Imagine directing an orchestra you can’t hear. Or playing a soundless piano for a staring audience.

Beyond composing without hearing a note, Beethoven grappled with living in the 1800s when few understood deafness, hindering his ability to communicate, work as a musician and even find a place to live. How he dealt with this deafness is one of the great stories of humanity, not just of music.

Beethoven began losing his hearing in his mid-20s, after already building a reputation as a musician and composer. The cause of his deafness remains a mystery, though modern analysis of his DNA revealed health issues including large amounts of lead in his system. At the time, people ate off of lead plates — they just didn’t know back then.

Beethoven even continued performing publicly as a musician, which was necessary for many composers of the age: That’s how they got their pieces out, not just composing but performing. For the longest time he didn’t want to reveal his deafness because he believed, justifiably, that it would ruin his career.

His condition didn’t go unnoticed, however. Composer Louis Sporh reacted to watching Beethoven rehearse on piano in 1814: “…the music was unintelligible unless one could look into the pianoforte part. I was deeply saddened at so hard a fate.”

Once his hearing was fully gone by age 45, Beethoven lost his public life with it. Giving up performing and public appearances, he allowed only select friends to visit him, communicating through written conversations in notebooks. His deafness forced him to become a very private, insular person over the course of time.

A common question is how Beethoven continued composing without his hearing, but this likely wasn’t too difficult. Music is a language, with rules. Knowing the rules of how music is made, he could sit at his desk and compose a piece of music without hearing it.

Beethoven’s style changed, however, as he retreated from public life. His once-vivacious piano sonatas began to take on a darker tone.

His famous Sixth Symphony also reflects his different life in deafness. Also known as the Pastoral Symphony, the musical work conveys the peace of the countryside, where Beethoven escaped city life after losing his hearing. In terms of his deafness, this was a very important symphony, reflecting the importance as an individual to keep his sanity by being in the country.

“How delighted I shall be to ramble for a while through bushes, woods, under trees, through grass, and around rocks” — Beethoven in a letter written in May of 1810

This and other pieces from his soundless years reflect his incredible grasp of composition. Beethoven was a master of the language of music, which is about the creation of sound, not about listening.

By California Symphony Music Director Donato Cabrera.

....impressionist nearly blind?

Because Claude Monet painted in his distinctive later style while diagnosed with severe cataracts.

Monet, a founder of French Impressionist painting, suffered from cataracts for much of his later life, during which time he produced some of his most characteristic work.

Both Monet and Edgar Degas had failing vision, but perhaps we don't appreciate what it meant to these artists. "It gives both new respect for what they could do with limited vision, but also gives us reason to re-examine perhaps what these paintings mean in the evolution of their style and work." Chris Riopelle, curator of 19th century paintings at the National Gallery, said: "I think there has always been a great mystery behind Monet and how much influence his eyesight had on his work."And the list goes on. Scientist, statesman, Tenor, Actor, Mathematician. For each of these people, the phrase "in spite of" isn't operative. "Because of" is closer, but it doesn't capture the full meaning. That disability is often a gift. It can make people better, not worse, different, not defective. The best of humanity.

No comments:

Post a Comment